|

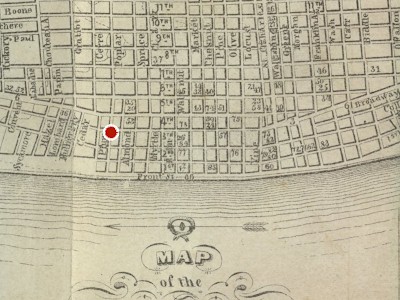

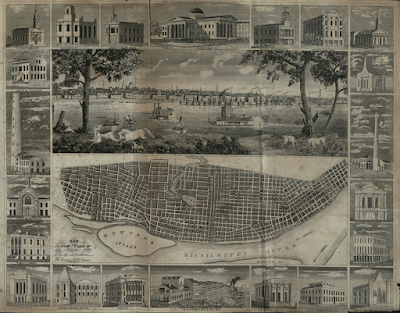

| St. Louis in 1840 showing location of St. Joseph School for Negro Girls and proximity to Mississippi River. |

|

| Sr. St. John Fournier |

AFTER EIGHT YEARS AND TWO MINISTRIES in the little village of Carondelet, Missouri, the small band of CSJ sisters was ready to take on a new mission in the bustling riverfront city of St. Louis.

The project, near and dear to the heart of Bishop Peter Richard Kenrick, was to be a school for the children of Black Catholics. But for the three sisters who made the short trip to St. Louis, the new mission – and their own charism to “serve the dear neighbor without distinction” – would soon put them in danger.

The Civil War was still two decades away, but St. Louis in the 1840s was already the epicenter of conflict and controversy over slavery. Slavery was legal, thanks to the infamous Missouri Compromise of 1820, but the white population was a volatile mixture of new organized abolitionist groups and old slave-owning French and American families. Violence was not uncommon.

Freedmen outnumbered slaves in the large Black population, and agricultural plantations were relatively few. That made St. Louis the scene of a stark and poignant situation – slaves toiling side-by-side with free Black workers in the city’s docks and shipping businesses. Along with that daily reminder of their enslavement, freedom was tantalizingly visible just half a mile away across the Mississippi River. Any slave who could cross it was free the moment he set foot in Illinois.

|

| Sr. Protais Deboille |

The school thrived for more than a year, according to a letter Sister St. John wrote in 1873. But it had reawakened simmering anti-Catholic sentiment in St. Louis and infuriated the slave owners. The slaves’ illiteracy kept then from reading abolitionist pamphlets and newspapers and causing trouble.

Many white Protestants objected to providing slave children and their parents with religious education. According to Sister St. John,

We also prepared slaves for the reception of the sacraments, and this displeased the whites very much. After some time, they threatened to have us put out by force. The threats were repeated every day.

It all came to a crisis one day in 1846.

|

| Miraculous Medal |

One morning as I was leaving the church, several people called out to me and told me that they were coming that night to put us out of the house. I said nothing to the sisters, and was not afraid, so great confidence had I in the Blessed Virgin! I put some Miraculous Medals on the entrance gate and on the fences (we already had them on all doors and windows of the house).

At

eleven o'clock, the sisters woke with a start when they heard a loud noise. Out

in the street was a crowd of people crying out and cursing. We recited together

the Memorare and other prayers. Suddenly, the police patrol came and scattered

those villains who were trying to break open the door. They returned three

times that same night, but [the Blessed Virgin] protected us and they were not

able to open the door from the outside nor to break it down... The day after

our adventure, the Mayor of St. Louis advised Bishop Kenrick to close that

school for a time and he did so.

The school never reopened, doomed a few months later when the Missouri Legislature passed law a making it illegal to provide any Black person with instruction in reading and writing. An exorbitant $500 fine was attached, equivalent to tens of thousands of dollars today. Nevertheless, the sisters quietly continued to give religious instruction to Black children.

Although they opened many other schools, that was the end of the St. Louis sisters’ teaching apostolate among American Blacks for almost 100 years, a century of agony that witnessed the Civil War, Reconstruction, Jim Crow and segregated schools. But during the Great Depression, true to their charism of recognizing a need and doing something about it, the sisters started offering a high-quality Catholic education to Black elementary and high school students in the city. It is impressive, but not surprising, that these schools were desegregated (by combining with the sisters’ white schools) years ahead of the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954.

Even after they were forced to close St. Joseph’s School, we like to imagine that the sisters continued to minister secretly among the Blacks of St. Louis in defiance of the authorities, going wherever the needs of the people drew them. Perhaps more than one Black child or adult learned to read and write through their help and love. We’ll never know, because the official records don’t tell these stories. But that would be the unstoppable CSJ way.

| ||

| St. Louis in 1845. Maps from University of Missouri St. Louis Mercantile Library. | |

The Mount Archives Blog owes a debt of gratitude to the the late Sister Jane Behlman, CSJ, archivist of the St. Louis Province, for writing about the school in her blog Jewels from Jane in 2008.