ONCE UPON A TIME, the name John Henry Newman was a familiar one on the campus of a Catholic college or university – a building, a club, a center. For much of its history, this was true at the Mount, too. The Newman Seminar Room was part of the original architecture of the Charles Willard Coe Memorial library in 1947 until it disappeared in the renovations of 1994-1996. The legacy continues to this day as the Newman Collection of rare books, papers and letters, which occupy an entire wall in Special Collections on the library’s first floor.

|

| Caricature of Newman in Spy Magazine in 1877 (MSMU Special Collections) |

Today, October 9, we celebrate the memorial of Newman as Saint John Henry Newman, canonized October 13, 2019, by Pope Francis. That his feast day is observed in the early fall of the academic semester is key to knowing who St. John Henry was. Among other things, he was a gifted essayist, novelist, and poet and a prolific one as well. But the work we care about is here is his 1852 The Idea of a University, which influenced the course of Catholic higher education and the liberal arts for the 20th Century and after.

Newman was a gigantic and hugely contentious political figure in 19th Century England. He was a renowned scholar, philosopher and cleric in the Church of England and popular professor at Oxford University. But while still a young man he began to harbor doubts about Anglican theology and starting publishing his questions in a series of pamphlets, or "tracts," sparking an uproar that lasted the rest of the century.

His eventual and very public conversion to Roman Catholicism in 1845 cost him and his followers their families, friends, homes and livelihoods. England was deeply anti-Catholic at the time, with a shocking bigotry that almost mirrors the racial ferment of 21st Century America, so it was no minor thing for Newman to change churches. He was ordained a Catholic priest in 1846 and resettled in Ireland to preach and teach in comparative poverty, and continued to write, often focusing on the problems of moral relativism, which he saw writ large in the Church of England. Not unlike Rev. Martin Luther King, his efforts and sacrifices over decades improved the lot of Catholics in England and he was able to return after 32 years, settling in the industrial city of Birmingham. He was made a cardinal by Pope Leo XIII in 1879 and died in Birmingham in 1890.

The careful reasoning and logic that led him to the Catholic Church made him a hero of Catholics in the United States, who were very much second-class citizens in the early 20th Century (and, believe it or not, regular targets of the Ku Klux Klan). Shut out of other elite schools, Catholics redoubled efforts to build their own colleges on Newman’s model, and further did him homage by forming Newman Clubs on almost every college campus in the country, religious or secular.

Newman was a big deal at Mount Saint Mary’s College. The 100th anniversary of his ordination to the priesthood fell on October 27, 1946, and was celebrated with an all-day symposium that included a dramatization of his long poem Dream of Gerontius, lectures by notable Hollywood Catholics and writers, a panel discussion, and choral performances of original compositions by the music faculty setting Newman’s prayers and poems to music.

|

| Members of the Newman Club gather in Brady Hall in 1953. |

Newman’s biggest fan at the Mount was Sister Catherine Anita Fitzgerald, CSJ, ’44, the leader who built Coe Memorial Library in 1947. It was she who insisted on the inclusion of the Newman Seminar Room in the blueprints and the one who filled it with books, art and antiques during her many years as head librarian and faculty member. In the 1950s she formed the Friends of the Library, whose first major fundraising effort was the purchase, at a Sotheby’s auction in 1960, of a large collection of Newman’s books, among them many rare first editions. To the Mount’s Newman Collection, over the ensuing decades, were added newer books as scholarship in Newman’s thought and influence grew and flourished. (Sister Catherine Anita herself wrote articles for scholarly journals and contributed an article about Newman for the Mount journal Inter-Nos.)

Other Newman scholars in Los Angeles have occasionally made the

pilgrimage to Chalon to use the collection, and it is still mentioned in

the Mount catalog as an important library asset. St. John Henry,

however, hasn’t been part of Mount life since the 1960s – either

in the classroom or at shared events with the Newman groups at USC,

UCLA, Loyola and Marymount. In some places, including MSMU, his

teachings on liberal arts and Catholic orthodoxy gradually fell out of

fashion after the Second Vatican Council in favor of more feminist or social

justice-oriented theologies. Sister Catherine Anita, Newman’s on-campus

champion, died in 1996 not long after the Newman Seminar Room ceased to

exist.

But we hold the collection in trust for the

future, because truth never goes out of style – a favorite principle of Newman himself. If you want to

commune with a genuine saint – after the Covid-19 pandemic, of course – come to the

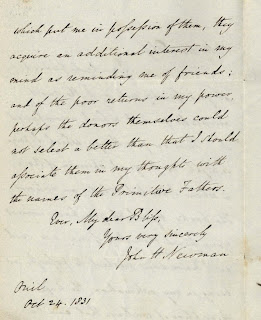

first floor of the library at Chalon where you will be welcome to

browse his books. In the meantime, we have digitized some of his handwritten letters from our collection (by the way, these are officially second class relics since he became a saint). The PDF will download to your computer. NB: You’ll need to be able to read tiny 19th Century cursive.

Our Lady of the Mount, pray for us. St. John Henry Newman, pray for us! Happy feast day!

|

| A second-class relic with Newman's cursive, from 1831 letter to James Bliss. (MSMU Special Collections) |